Hello,

You have landed on Brendon Bosworth’s old and archived website.

To get in touch about Brendon’s communications work please visit: www.humanelementcommunications.com

Brendon’s photography site is live at www.brendonbosworth.com.

Thanks!

Hello,

You have landed on Brendon Bosworth’s old and archived website.

To get in touch about Brendon’s communications work please visit: www.humanelementcommunications.com

Brendon’s photography site is live at www.brendonbosworth.com.

Thanks!

Hi. If you’ve landed here and want to read about what I’m up to with photography please visit my photography site.

Thank you,

-Brendon

I wrote previously on the benefits of shooting with one camera (Ricoh GR II) with a fixed lens and how that has helped me learn a lot about photography over the past year or so.

One of the main things I’ve learned is that what at first can seem like a limitation can be turned into something useful. I’m talking about the apparent disadvantage of working solely with a 28mm focal length, especially in situations where it might be better to have a longer focal length.

I’m typically a fan of close-up street shots and getting right into the mix with things I photograph. That sort of photography suits the GR, since the wide angle really requires that I get up close to things to translate the energy of the moment into a good photo. The shots I’m most proud of are usually quite busy. They’re filled with subjects and convey a sense of movement. However, I also like a more contemplative approach to photography. One that involves capturing single subjects interacting with their environment in ways that gives an impression of people finding moments of stillness.

Shooting at 28mm makes it pretty tough to get those kind of shots right. The major issue is that often it just feels like I’m shooting from too far away. Sometimes when I spot one of these moments of stillness — a person balancing in a tai chi pose in a busy city’s park, or a family knee-deep in the ocean, watching a storm come in — and line up the shot I find myself thinking, ‘I really need a longer lens.’ But what I’ve begun to notice with these types of shots is that I actually like the way people in them are rendered small in comparison to their surroundings. The way the wide angle lens pulls in so much of the world around the subjects, and makes them look a bit tiny in the vastness of it all, reminds me of how we’re all making our way through this big world and despite all the constant motion can find points of stillness wherever we are. The presence of the surrounding environment — trees, beach, open sky — also reminds me of how what’s happening around us affects us, whether we notice it or not. These photos let the world in.

The more I shoot with the one camera/one lens set-up the more I realize how it’s possible to take what might initially seem like a limitation and turn it into something positive. I’m slowly starting to collect more of these ‘moments of stillness’ shots and hope to have a strong collection within a few years time. I feel like they’re slowly starting to become part of my style and that feels like a good thing.

I recently made a website for my photography. In my first blog post, I share some of the lessons I’ve learned shooting with a compact fixed lens camera, the Ricoh GR II, over the last year.

….

When I started getting more into photography in 2016 I read a good bit of advice: pick a camera and lens setup and stick with it for at least a year. I have found that bit of wisdom to be challenging and rewarding in the year I have owned and shot pretty much exclusively with the Ricoh GR II.

If you’re not familiar with the GR line of cameras, the GR II is a compact camera with a fixed 28mm equivalent lens. It comes in all-black, has a crop sensor (APS-C), shoots RAW, and produces high quality images.

Learning with a fixed lens

Shooting with a fixed lens has taught me a lot about photography. I’m glad I started my photographic journey with a fixed, wide lens. When I started out with the GR I found shooting with the 28mm tough to deal with. Most of my shots were taken from too far away –- subjects looked tiny, drowning in far too roomy frames. Shooting on the street was the most difficult. I had the fear of getting close enough to strangers to make good street shots (you really do need to get close with this camera). I was mostly frustrated.

But slowly I started getting accustomed to the wide angle, and making sure I was closer to the people and things I wanted to shoot. Having the GR II has pushed me to interact with the scenes and characters I find interesting to photograph. It’s also helped me get more comfortable taking really close up portraits of people (although, admittedly, I still find this a bit nerve-wracking). Approaching a stranger in the street for a portrait is one thing. Standing right up close to them to shoot it is another since most people aren’t so used to having a camera a few inches away from their nose, unless it’s for selfies.

I have also realized that with a wide lens I really need to pay attention to what goes on at the corners of the frame. With a wide lens it’s easy to get more than you bargained for in your pictures. I still blow lots of shots with unwanted poles, body parts, heads, and general background distractions. I still find myself saying ‘should have got closer’ when editing my photos. But this challenging aspect of shooting with a 28mm is helping me frame my shots better.

Joys of a small camera

There is a line that seems mandatory in any review of the Ricoh GR II: ‘this camera fits in your pocket.’ I never carry my camera in my pocket because I am paranoid about afflicting it with the dreaded sensor dust (read Matt Martin’s post on this issue over at endlessproof.com). But the Ricoh GR is so small and compact that it takes up hardly any space in my little backpack, which means I end up taking it along on walks around my neighbourhood, my travels, or to be used for a quick 30 minutes after a meeting, or sometimes just when strolling around new cities. There is no doubt that the more time spent with camera in hand translates to better shots and a more intuitive understanding of the camera itself.

Becoming intuitive

Shooting with just one camera with a fixed focal length means that eventually the camera, and its strengths and weaknesses, becomes something you understand without thinking too much about it. After firing off thousands of frames with the GR II it feels like I have a better understanding of where to aim, how close to be, and what settings to use to get the shots I want than when I bought it a year ago. I know what the camera is and isn’t capable of (it’s not a good low light performer, for one). That said, I also know how easy it is to make bad photos. I know when I’m not working the camera properly and using it the way it needs to be used. If I go a week or so without shooting, it’s guaranteed the first day or so shooting will not result in any good pictures. On the other hand, if I’ve been shooting every day for a week I’ll usually be feeling a lot more confident and dialed in, not thinking too much about the camera, framing shots quicker. This, typically, is when I’ll make a good picture or two. From what I’ve learned so far, using the camera regularly and having it in hand as often as possible means that I can make shots more intuitively. Being totally in sync with the camera and process of making good pictures still doesn’t happen as often as I’d like. I’m still learning. But I’ve felt moments of being in a zone where shooting feels intuitive and I know that more time with the GR in hand will lead to more of this in future.

I no longer treat the GR like a baby

I spent a long time finding my camera, searching online for a good deal. I got a good deal on a used GR that the previous owner had kept in fine condition. I promptly bought a case for it and made sure to keep it in there whenever not in use. But life happens. A few months into my ownership my partner accidentally knocked the camera (sans case) off the bedside table. It dropped onto the floor with a less than appetizing thud. When I picked it up (cradling it like a wounded bird just dropped from the nest) I noticed that the front lens cover plate had popped out from where it joins the lens barrel. I wasn’t sure how bad this was but figured it wasn’t healthy. First I freaked out — way more than was necessary. Then, I got over myself and pushed the dislocated piece back in. A couple of test shots showed no difference in image quality. I carried on living.

That first drop was good for me. After that I stopped treating the GR like it was made of glass. It’s just a camera after all. And it’s capable of taking some knocks.

A few months later, I met a sand sculptor at the beach who was sculpting a sea snail in the sand. I spent an hour or so shooting him, making sure to keep sand off my lens. It was great. Then, just before I was ready to head home, but still trying to squeeze off a few more shots, he flicked a globule of wet sand straight onto the lens (by mistake. He was working with sand, after all). It landed on the glass and went into the lens cavity. Not great. For some reason, I thought the sand might make some kind of artistic blur effect and actually took a few more shots with it on the lens before realizing what a bad idea that was. I then ran home to get a vacuum cleaner. I locked the pipe’s end onto the lens and sucked out all the sand I could. Got most but not all of it. I then spent ages with a blower, lens brush, and piece of paper getting the last grains of sand off the glass and out of the lens cavity. However, a smear of saltwater remained on the glass, providing a proper blur effect. But not the kind that’s of use to anyone.

Also, the blades that close when you switch the camera off to protect the lens were jammed. This filled me with the fear of scratched glass in future. I headed to my local camera shop. They couldn’t fix the blades and told me it wouldn’t be worth the cost to do it. The guy behind the desk took my camera into the backroom and wiped the lens down with window cleaning fluid. (I later read that using a vacuum cleaner to suck dirt out of your camera is not a good idea. But it seemed to best option at the time).

Since then, I have kept my camera in its bag without the lens blades closing properly and haven’t picked up any scratches from what I can tell. I also read this article that says lens dirt and scratches on the front element aren’t actually the worst thing in the world, anyway.

I have found my journey with the Ricoh GR II difficult at times. There are loads of bad photos on my hard drive — shots taken from too far away, shots filled with superfluous background objects, shots with missed focus, the usual. And I know I’m still working toward making my best shots so far. But I imagine this is pretty much typical of anyone starting out with photography. Ultimately, using one camera has been very rewarding, even if I do sometimes find myself wishing I had a 50mm lens. If I look back through my archives, I see a gradual transition to better photos as I’ve become more competent with the GR. It’s good to be able to look back over thousands of frames and see some improvement. I know a lot of this is just due to shooting as much as possible with a camera that I know well. These days, the GR feels right at home in my hand and that’s all I need from a camera.

All images © 2016-2017 Brendon Bosworth.

If you’re interested to see more of my photography please visit my site: https://brendonbosphotography.wordpress.com/

My first article for Groundup…

By Brendon Bosworth

24 March 2016

Shuaib Hoosain is the treatment manager at Sultan Bahu, a rehabilitation facility in Mitchells Plain. Brendon Bosworth.

After 16 years of injecting and later smoking it, Letitia Wyngaard wanted to quit heroin. Her father was ill and she needed to help take care of him. She wanted to be a mother to her two young boys, who she had alienated as she oscillated between the aggression that comes when craving the drug and being “the most lovable person ever” when she had it.

“My son said, ‘if you don’t have that white stuff you’re like a vampire. When you have that white stuff then you’re okay, mommy,’” she recalls. “I didn’t want them to live that life.”

On the advice of a friend who had turned her back on the drug that is notoriously tough to quit, Wyngaard booked into the Sultan Bahu Centre, a rehab in Mitchells Plain named after a Sufi poet. The centre is just a few streets away from where she lives.

Following a detox at Stikland Hospital’s Opioid Detoxification Unit, Wyngaard began treatment at Sultan Bahu. At the centre, a modest two-storey building with yellow walls and a sign that reads “optician” outside — a remnant of its former life as a medical centre — she started taking medication that fends off the harrowing withdrawal symptoms that come when heroin users don’t have the drug in their system.

Withdrawal is “the worst feeling ever,” explains Wyngaard. “You have back pain, you have sweats; your nose is running, your eyes are tearing. You literally can’t walk, especially when the ‘turkey’ really hits you.”

Acting on the same receptors in the brain that heroin works on, a medication called Suboxone curbed the withdrawal symptoms without giving her the heroin high. Suboxone is a combination of the medications buprenorphine and naloxone.

“The Suboxone helps you not to crave,” says Wyngaard. “It’s almost like a crutch. It takes those exit pains away.”

With her treatment keeping the pain and cravings under control, Wyngaard was able to engage with the counselling sessions at Sultan Bahu. She learned about ways to prevent relapse and methods for coping with situations that might drive her to use heroin again, as well as staying clear of people linked to her life as a heroin user. Through one-on-one sessions with the centre’s social worker she learned how to face her own issues.

“I came in with a lot of baggage,” she says. “I used to try and smoke that feeling away and all my feelings [were] coming back, so I had to deal with that.”

After taking Suboxone daily for the first three months of treatment, Wyngaard was gradually weaned off it during a further six months until she was able to stay off heroin without the medication. Almost two years later, she remains free of heroin and still comes into the centre twice a week for “aftercare” sessions, where she can discuss her feelings and any problems she might be having.

Now, expecting her third child, she speaks about her past and present with a calm resolve that underplays what must be a great inner strength.

The treatment Wyngaard underwent is called medication assisted treatment (MAT), better known in South Africa as opioid substitution therapy. It involves treating someone addicted to heroin with medications like buprenorphine, naloxone and methadone so that users can feel ‘normal’ while undergoing therapy. It is used in many countries, and when coupled with psychosocial interventions was found to be the most effective treatment option for opioid users, according to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

Sultan Bahu’s programme is yielding promising results. Its current “retention rate” — the rate at which clients keep up their treatment — is 93%, says Shuaib Hoosain, the centre’s treatment manager. And 82% of clients were “drug-free” when last tested, according to Hoosain. Such high rates could be due to the Centre carefully selecting the clients for the programme and keeping them motivated, as well as doing things like follow up phone calls and house visits if clients aren’t attending.

Importantly, clients, most of whom are unemployed, are sticking to their treatment, which requires coming to the centre from 8am to 4pm daily. This means they are not on the streets looking for heroin or stealing to support their habits, reducing the harm to themselves and society.

“It costs significantly less to keep somebody on [MAT] than society would pay to have the person in prison, or [for the cost of] the damages the person would cause as a result of acquiring the drugs,” says Hoosain.

Estimates by the World Health Organisation indicate that every dollar invested in opioid dependence treatment programmes may give a return of between $4 and $7 in reduced drug-related crime, criminal justice costs and theft.

Despite the successes of MAT at Sultan Bahu and its widespread use elsewhere, South Africa has not embraced this treatment option. Sultan Bahu is billed as the only rehab in the country where clients can get government-funded MAT medication free. The Western Cape’s Department of Social Development has funded the programme since its inception in 2014, the year Wyngaard booked herself in.

People dependent on heroin are a vulnerable group. They die at a rate that is between six and 20 times higher than expected for people of the same age and gender in the general population. Those who inject the drug, instead of smoking it, face the added risk of contracting HIV and other diseases from infected needles.

Hoosain says he is seeing more people who inject heroin coming into the centre. Many former tik (methamphetamine) smokers have also graduated to heroin, sometimes using both drugs together. “The guys I saw, previously, using methamphetamine back in 2007, all of them are using heroin,” he says. “And I’m not exaggerating.”

In the Western Cape, 14% of people admitted to rehabs reported using heroin as their primary drug of abuse in the first half of 2015, according to figures from the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use.

Sultan Bahu treated 84 patients in the MAT programme’s first year and 94 in the second year. But the demand for treatment far outstrips the centre’s ability to provide it, says Hoosain.

At this point, however, government is not set to beef up its funding.

The Western Cape Department of Social Development earmarked just under R2 million for the programme for the 2015/2016 financial year and is funding it for a third year, according to Sihle Ngobese, spokesperson for Albert Fritz, the province’s Minister of Social Development

But due to the costly nature of treatment the programme’s sustainability will depend on partnerships with the Department of Health and pharmaceutical companies, he says. The Department won’t be extending the programme to other rehabs either due to budget constraints.

Outside Sultan Bahu and private rehabs, heroin users can get MAT therapy at Stikland Hospital and Groote Schuur Hospital, but need to pay for the medication themselves, sourcing it from private pharmacies. With the high cost of Suboxone, treatment can be out of reach especially for those who are unemployed.

It costs about R125 for a seven-pack of 2mg Suboxone tablets. For a pack of stronger 8mg tablets it’s about R500. With treatment running for between three and six months, and in many cases longer, costs quickly rack up.

The steep price tag means the MAT clinic at Stikland often has to prescribe lower doses of medication. But skimping on medication means an increased chance that people in treatment will use heroin while undergoing MAT instead of staying clean.

“The worry [with] under medicating patients using too low doses is that they still have breakthrough slips on heroin. The higher the dose the better they can stay clean but the more expensive it becomes,” says psychiatrist Lize Weich, coordinator of addiction services at Stikland Hospital.

“We often end up under-prescribing because that’s all that people can afford. But under-prescribing is already better than no prescribing when we think about retaining patients,” she says.

“What’s worse?” says Weich. “Using 12 bags of heroin a day, or using one twice a week and coming back and seeing the doctor and working on what were the triggers, high risk situations, and how can I manage my life differently so that I don’t use that once or twice?”

Stikland and Groote Schuur are the only two facilities nationally to offer MAT treatment like this, and the Department of Health can’t expand the service due to the current financial state of the country, says Bianca Carls, spokesperson for the Western Cape Department of Health.

“These medications are exceptionally expensive and when compared to medicines required for ailments such as HIV/AIDS and chronic [health conditions], it is the duty of the Department to prioritise which medications are essential for our patients,” she says. Importantly, though, methadone and buprenorphine are listed as essential medicines by the World Health Organisation.

For those who get into Sultan Bahu’s MAT programme the cost of medication is not a problem. And for people like Wyngaard the programme has proved to be a life-changer. Whether or not more heroin users have a chance to follow the same path remains in the hands of government.

Published originally on

GroundUp

.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

After a week of student-led protests around the country, President Jacob Zuma announced today that South African universities will not increase their fees in 2016, signalling a win for the #feesmustfall campaign. At Stellenbosch, students heard this news while waiting outside the police station for the release of some fellow protesters arrested earlier in the day. I shot some photos.

After a week of student-led protests around the country, President Jacob Zuma announced today that South African universities will not increase their fees in 2016, signalling a win for the #feesmustfall campaign. At Stellenbosch, students heard this news while waiting outside the police station for the release of some fellow protesters arrested earlier in the day. I shot some photos.

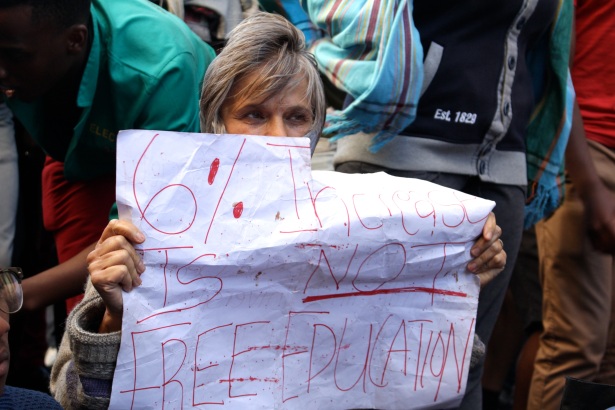

Student protests against university fee increases intensified across the country yesterday. In Cape Town, hundreds of protesters demonstrated outside parliament where Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene was delivering his mini budget speech. Protesters are demanding that the planned fee increases for 2016 be scrapped, and have rejected a deal struck between Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande and university vice chancellors on Tuesday that would see fee increases for 2016 capped at 6%.

Student protests against university fee increases intensified across the country yesterday. In Cape Town, hundreds of protesters demonstrated outside parliament where Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene was delivering his mini budget speech. Protesters are demanding that the planned fee increases for 2016 be scrapped, and have rejected a deal struck between Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande and university vice chancellors on Tuesday that would see fee increases for 2016 capped at 6%.

My latest article for Citiscope takes a look at Melbourne’s 1200 Buildings program, which the city launched in 2010 to encourage energy-efficiency upgrades to commercial buildings so that they guzzle less water and electricity. Read the intro here and go to Citiscope for the full story.

MELBOURNE, Australia — The octagonal office tower that sits above a Maserati dealership here has seen a lot of change since it was built for an airline tycoon in the late 1970s.

For one thing, the helipad on the roof has been replaced with a black “plant room.” This space houses the mechanical guts of the building’s new heating and cooling system — a much more energy-efficient version than its predecessor.

The current owners also installed new elevators that use a regenerative braking system to generate power for the building. These upgrades were part of a retrofit completed earlier this year. The changes cut the building’s energy bills by 25 percent, producing energy savings equivalent to removing the carbon emissions of 55 homes a year.

“We wanted to update the plant and the lifts so we effectively had a ‘brand new building’ with a shell from 1979,” says Barry Calnon, chief financial officer at PDG Corporation. PDG is a large developer and manager of commercial and residential buildings in Melbourne. It co-owns the tower at 501 Swanston with Bobby Zagame, who owns the Maserati dealership as well as an Audi dealership downstairs.

Calnon, looking sharp in a navy blue suit with a set of little silver cars for cufflinks, explains that the retrofit was part of a larger refurbishment meant to attract premium corporate tenants. It cost a few Maseratis’ worth, and was paid for with a US$5 million loan through a Melbourne City Council fund for financing energy-efficiency upgrades in commercial buildings.

The retrofit at 501 Swanston is just one of many undertaken through the city of Melbourne’s 1200 Buildings program. It’s a multi-pronged strategy launched in 2010 to encourage energy-efficiency upgrades to commercial buildings so that they guzzle less water and electricity. The office buildings that dot the skyline in Australia’s fastest-growing and “most livable” city produce more than half of its greenhouse gas emissions. That needs to change if Melbourne is to reach its ambitious goal of being carbon-neutral by 2020.

– See more at: http://www.citiscope.org/story/2015/what-melbourne-learned-cutting-emissions-1200-buildings#sthash.8DYudu0G.dpuf

The short film Simon Taylor and I produced, ‘Normal’ screened at the SA Recovery Festival in September. The film is a 16-minute documentary that gives a window into the work of psychiatrist John Parker, who I wrote about for the ‘City Desired‘ exhibition. It includes Mykyle, one of Parker’s patients who is in recovery.

The short film Simon Taylor and I produced, ‘Normal’ screened at the SA Recovery Festival in September. The film is a 16-minute documentary that gives a window into the work of psychiatrist John Parker, who I wrote about for the ‘City Desired‘ exhibition. It includes Mykyle, one of Parker’s patients who is in recovery.

The film shows how John and Mykyle are both outsiders. One is a doctor who works in a

community very different to his own. The other is unfairly placed outside of what society considers ‘normal’ due to the stigma around mental illness. It shows the value each of them brings to the

world and takes an honest look at the subject of mental illness, something that afflicts as many as one in three adult South Africans in their lifetimes.

Simon and I were pleased to see how many people came to watch the film. After the screening, we had an engaging question-and-answer session that highlighted the importance of understanding mental illness and how it impacts our society. We came away motivated to work on our next project, a longer film we are developing.

Last year, as part of the African Centre for Cities’ City Desired project I wrote an in-depth profile about Dr John Parker, a psychiatrist based at Lentegeur Hospital. This psychiatric hospital in Mitchells Plain, on the Cape Flats, is at the front line of treating methamphetamine-related psychosis in Cape Town’s poorer communities. If you’re up for a long-read that address issues of mental health, drug abuse, social deprivation, hope and recovery, my piece is available online and will also be out in Cityscapes magazine soon. Photo: Sydelle Willow Smith.

Photo: Sydelle Willow Smith.